In Why Grow Up? Subversive Thoughts for an Infantile Age (2014), Susan Neiman describes being grown up as “renouncing your hopes and dreams, accepting the limits of the reality you are given, and resigning yourself to a life that will be less adventurous, worthwhile and significant than you supposed when you began it” (1), thereby debasing the often-idealised phase of adulthood. Vanessa Joosen has demonstrated how ageist tropes depicted in children's literature, such as “the decline narrative, the infantilized senior, the disregard of the old body, and the wise old mentor" (2015: 128), can be contextualised through the lens of age studies. The life phases of childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age are often depicted in narratives by means of such ageist stereotypes.

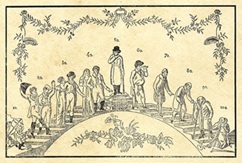

To study such broad-ranging implications of the lifespan, the interdisciplinary field of age studies includes scholars from the fields of biology, sociology, gerontology, developmental psychology, anthropology, and cultural studies, among others. Age scholar Susan Pickard points to the medieval wheel of life, evoked by Robert de Lisle’s “Wheel of the ten ages of man”, which was replaced by an approach based on life stages as a staircase “rising and falling in a pyramid shape with all its connotations of progress followed by decline” (2016: 69). Nowadays, the life course has broken down, its “standardised and institutionalised character lost” (Pickard 2016: 70). Even though age is an equally important identity marker on the spectrum of gender, ethnicity, religion, class, race, nationality, and so on, it is often taken as a given (Pickard 2016: 47). Yet what about 70-year-old teenage dirtbags and 7-year-old sprinters who think old people are slowpokes?

To study such broad-ranging implications of the lifespan, the interdisciplinary field of age studies includes scholars from the fields of biology, sociology, gerontology, developmental psychology, anthropology, and cultural studies, among others. Age scholar Susan Pickard points to the medieval wheel of life, evoked by Robert de Lisle’s “Wheel of the ten ages of man”, which was replaced by an approach based on life stages as a staircase “rising and falling in a pyramid shape with all its connotations of progress followed by decline” (2016: 69). Nowadays, the life course has broken down, its “standardised and institutionalised character lost” (Pickard 2016: 70). Even though age is an equally important identity marker on the spectrum of gender, ethnicity, religion, class, race, nationality, and so on, it is often taken as a given (Pickard 2016: 47). Yet what about 70-year-old teenage dirtbags and 7-year-old sprinters who think old people are slowpokes?

In his recent book Bye Bye I Love You (2025a), Michael Erard explores connections between first and last words, as cultural, interpersonal and linguistic artefacts bookending our signifying selves, when our linguistic powers are emerging or waning. As he writes, "If you’re the one on the scene with intact, mature language abilities, you find yourself asking, Is that a grimace of pain or a smile? Is that a babble or my name? Is this an utterance from the organism or the expressive self? Here the stakes seem immense – if someone isn’t producing language, who are they?” (2025a: 15).

First and last words provide an interesting site of investigation to remind us that linguistic meaning-making is always co-creation, a social ‘doing together’ in specific cultural and historical contexts, emerging from a desire to interact; and that it is a multimodal, whole body event involving, alongside words or signs, also gestures, facial expressions, gaze direction and shift, nods, blinks, postures and the like (Perniss 2018, Holler & Levinson 2019, Özyürek 2021) – and silences too, so often communicatively relevant (Hoey 2020).